The Europeans who first sailed to Newfoundland came because of fish. And fish determined the type of settlement that was made, as well as the early and enduring structure of Newfoundland society. In the beginning, the fish traders wanted to control the seasonal fishery from home ports in England. Since they did not want the fishermen to stay here, they made rules and laws to discourage the possibility of any such settlement. But the fishermen settled anyway, rugged individualists that they were (and continue to be), eventually forcing the fishery to be based on the island. They and their families, scattered along nearly 10,000 thousand kilometres of jagged coastline, fished for their living; they cut their own lumber and fuel; they built houses and boats; they killed seals, raised poultry and small livestock, grew vegetables, hunted and trapped. They were builders and survivors. And they rarely saw cash. Their fortunes and misfortunes, as Gordon Inglis wrote, were to be found in the entries of the merchants' ledgers.

In the late 1800's nearly 90% of the male workforce in Newfoundland was occupied in the fishery. But while these fishermen, who had come mainly from the west counties of England and from the southeast counties of Ireland, struggled to make a decent living, they were hopelessly dependent on the merchants who determined not only the price they would pay for fish but also the cost of fishermen's supplies.

One of the first attempts by fishermen to overcome the debt-credit system was made by the fishermen of Carbonear and Harbour Grace in 1832. No sooner had they undertaken to band themselves together to demand a just price for their fish when a Proclamation was issued by the Chief Justice in St. John's forbidding the formation of any such group of fishermen and threatening them with the full weight of the law if they attempted to do so. The same proclamation offered a reward of 100 pounds sterling (an extraordinary amount for those times) to any person who would provide information regarding the fishermen who, in an act of anger and frustration, had damaged the sail and spar of a local merchant's ship. Intimidation and fear held the day. The fishermen's early efforts for fair treatment died quickly.

In 1840 large groups of fishermen going to the ice for the sealing season marched on St. John's to protest the conditions of their employment: they were being forced to pay "berth money" to secure a position on the sealing vessels and were forced to contribute up to 33% of the supplies they used while on board. Ship owners and merchants paid little attention to their requests and the unjust system continued for years.

During the second half of the nineteenth century efforts were made to organize the fishermen of Newfoundland. The Hearts Content Fishermen's Society was formed to provide sickness and death benefits for fishermen and their families. The Anglican sponsored Society of United Fishermen (SUF) was similar in nature. The Catholic counterpart of these groups was the Star of the Sea societies. But these and similar organizations lacked any real power or political strength; as a result, working conditions and pay issues were never really addressed. Such efforts had little effect on the traditional merchant/fisherman relationship. The fishermen's sense of powerlessness prevailed and the hopeless and persistent cycle of debt remained a sad reality.

The first real attempt to mobilize the fishermen of the island into a union began in 1908 at Herring Neck in Notre Dame Bay when William Ford Coaker, a man born and raised in St. John's (and who had organized his first strike of waterfront boys when he was fourteen years old) managed to convince 19 men to begin a union. Within five years, Coaker, a brilliant and charismatic leader, had signed up 15,000 men in the Fishermen's Protective Union (FPU), communicating with them through the union's own newspaper, The Fishermen's Advocate. Ridiculed by merchants as the "Messiah of the North," Coaker answered his critics by establishing effective union locals and branches along the northeast coast and setting up union stores through the newly formed Union Trading Company which challenged the oppressive credit system and helped reduce fishermen's expenses. Since he believed that the only true road to reform the fishery was the political route, he organized the FPU into a political party to contest the General Election of 1913. The FPU's "Bonavista Manifesto" was a 31 point program to bring about reform and was the union's election platform. It was a visionary program far ahead of its time and included proposals for elected school boards, free and compulsory education, a system of night schools, old age pensions to all people over seventy, a long distance telephone system, minimum wages, standardized cull, weekly reports on prices in foreign markets, reduced duties on fishing gear, food and bait and new laws for the conduct of the seal fishery.

Eight of the nine FPU candidates who contested the 1913 election were elected to the legislature. It was a stunning victory. A new force in Newfoundland political history was born. Coaker moved quickly to have the governing People's Party implement the FPU's fisheries reforms. But the intervention of the First World War and the ruling government's political manoeuvres allowed little in the way of reform. At the end of the war, in the election of 1919, the FPU and the Liberals formed a ruling coalition party governing Newfoundland and Coaker introduced his reformed fishing regulations. The post-war depression prevented their effective implementation. Fish prices fell, Newfoundland exporters panicked, the market collapsed. The party went into decline. Coaker's dream faded and in 1926 he resigned his position as head of the union. The FPU party soon lost its political identity. In 1932 the once-vibrant "new Moses" retired from the government and the FPU days of glory were over. It would take nearly forty years before Coaker's vision of a unified and powerful union of Newfoundland fishermen would once again emerge from the shadows to the light of new life.

In 1951, Joseph Smallwood, then Premier of Newfoundland and a man with a strong labour and union background, invited over 200 fishermen at government expense to come to St. John's to hold a convention and establish a federation of fishermen. Though modelled on the FPU, the new Newfoundland Federation of Fishermen (NFF) had none of Coaker's vision, energy or independence. It collected only nominal federation dues and was almost entirely dependent on the government for funding. The NFF, with a leader hand-picked by the government, could not, because of provincial labour laws, engage in collective bargaining on behalf of the fishermen of the province and refused to affiliate with the Canadian Labour Congress (CLC). The Federation was doomed to be powerless and ineffective.

1969 was a bad year for Newfoundland fishermen - as were the two years which preceded it. Fishermen had little choice but to accept the buyers' prices - prices which were on a downward slide. Within a year, 200 fishermen had come together in Port au Choix to fight back. Several months earlier they had asked a parish priest, Father Desmond McGrath, to help them in their plight. Given his own working background and his association with the social gospel of Moses Coady of he Antigonish Movement, McGrath suggested to the fishermen that they consider forming a union. And he went further. He asked a former classmate from St. Francis Xavier University, Richard Cashin, a St. John's lawyer from a politically legendary family and former Member of Parliament, to assist him and the fishermen in a business none of them were familiar with - establishing a union. The dynamic Cashin put aside his initial hesitation, and on an April day in 1970 the Northern Fishermen's Union (NFU) began with a fresh charter and constitution.

Over the next several months McGrath and Cashin criss-crossed the island speaking to groups of fishermen and working tirelessly to expand the organization. But they lacked the financial resources and professional organizers to complete the job adequately. In April of 1971 the first convention was held at which Richard Cashin, a natural and aggressive leader, was elected the union's first President and Kevin Condon, a fisherman from Calvert and former executive member of the NFF, its Vice-President. By September of the same year, and now working with the assistance of Ray Greening, an experienced and energetic organizer, the union had worked out an agreement to merge with the Canadian Food and Allied Workers Union (CFAWU). Three plant workers' locals at Trepassey, Harbour Breton and Port Union and the NFU ratified a new charter to become the Newfoundland Fishermen, Food and Allied Workers' Union (NFFAWU).

"If they think I'm going to be dictated to by priests, lawyers or gangsters from Chicago, they've got another thing coming." So declared Spencer Lake to reporters when asked about the NFFAWU's attempt to unionize the plant workers at his Burgeo fish plant on the south coast of Newfoundland in the spring of 1971. Lake threatened to sell the plant if the workers voted for a union. Despite the threats the workers did vote narrowly to join the NFFAWU. When the first negotiations with the plant began the town was divided and Lake treated the union's demands with contempt. A clash was inevitable and on June 3, 1971 the plant workers voted to strike.

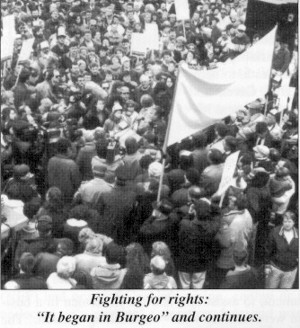

Non-union workers and students crossed the picket lines. Union members blocked the roads leading to the plant. Workers were brought in by boat. Floating pickets were set up around the wharf. Violent confrontations loomed. The strike dragged into weeks, then to months. The battle in Burgeo was taking on historic proportions. "What happens here in Burgeo," Father McGrath had said, "will reflect the quality of life in Newfoundland for generations to come." Meanwhile, Smallwood's government, with an election approaching, refused to intervene. The union campaigned for public support. Fellow unions donated monies, called for sit-ins and held rallies on the NFFAWU's behalf. Shortly before the fall election, the strikers vented their frustration in an outburst of anger, damaging plant premises. Conservative leader Frank Moores promised to settle the dispute if elected Premier. The October 26 election ended in a tie. It was two months before Moores became the Premier, but he kept his promise. The government bought the plant, and in March of 1972 an agreement was signed with the plant workers. The Burgeo strike had proved the workers' and the union's mettle. It was a landmark victory for the NFFAWU.

In 1973 the union signed contracts with fish companies providing for a 72% wage increase over two years; grievance procedures were put in place; a seniority clause was introduced, along with paid holidays and a health plan. A year later trawlermen across the island tied up their boats because they believed that it was not the price of fish they should negotiate with companies but rather the income level that would be attainable for full-time work. Within the year the union saw a significant achievement: an agreement which did away with the concept that trawlermen were, like the plant - and fish company owners, "co-adventurers." The struggle was long and difficult but the gains for fishermen were enormous. A centuries-old relationship between fishermen and fishbuyers had been changed and wages, in some cases, rose from $8,000 to $14,000 annually.

When fishermen could not find local fish plants to take their catches of squid and mackerel in 1979, the union, with the blessing of the federal fisheries department, negotiated with Bulgaria and Sweden to sell their fish directly to the foreign factory ships. The provincial government and local fish companies were outraged and complained to the Federal Minister of Fisheries that the union had assumed the role of fish merchant, thus affecting the market price of these species. The union prevailed over the objections, however, and in that year alone fishermen earned $6 million through their "over the side" sales.

A crucial year in the history of the union was 1980 when a 13 week strike brought about major improvements in wages and working conditions for 2,300 employees of Fishery Products Limited. In the same year, fish buyers unilaterally dropped some fish prices and discontinued the deduction of union dues, affecting fishermen in the inshore sector. The union called a strike in selected ports which triggered a massive province wide lockout. After a five-week tie-up, the fishermen succeeded in gaining improved fish prices and re-establishing dues deduction by the fish companies.

A recent and innovative move by the FFAW was the creation of the Labrador Fishermen's Union Shrimp Company. The vision and energy of President Richard Cashin and others led to the fishermen of Labrador gaining licensed access to the shrimp resource off northern Labrador and setting up a new enterprise. The company, share-owned and operated by Labrador fishermen, also oversees the operation of shrimp plants. It has become a mainstay of the Labrador fishery and is a creative and genuine success story.

The spirit and dedication which gave birth to the union in 1970 still animates it today. The union, under the progressive leadership of President Earle McCurdy and Secretary-Treasurer Reg Anstey, continues to search for ways to improve the working conditions and the lives of its members. In 1987 the NFFAWU decided to break away from its international affiliate and join the Canadian Auto Workers (CAW), become the FFAW/CAW. The CAW is a Canadian union known for its progressive style and dedication to the education of its members. With the assistance of the national union the FFAW/CAW has become very active in the education/training area, promoting the idea of peer teaching in programs such as LifeLine whereby fisherpersons teach fisherpersons, plant workers teach plant workers, trawlermen teach trawlermen; Fishermen's Resource Centres along with Education Centres have been established and education programs are coordinated to deliver training to members throughout the province.